Small and shy by nature and with trunk-like noses, saiga antelopes seem like unlikely survivors of the Pleistocene. Yet they’ve endured long after the mammoths and their other ancient megafaunal contemporaries went extinct. Today, the last stronghold for the species is the vast steppe ecosystem of Kazakhstan, which holds about 99% of the global saiga population.

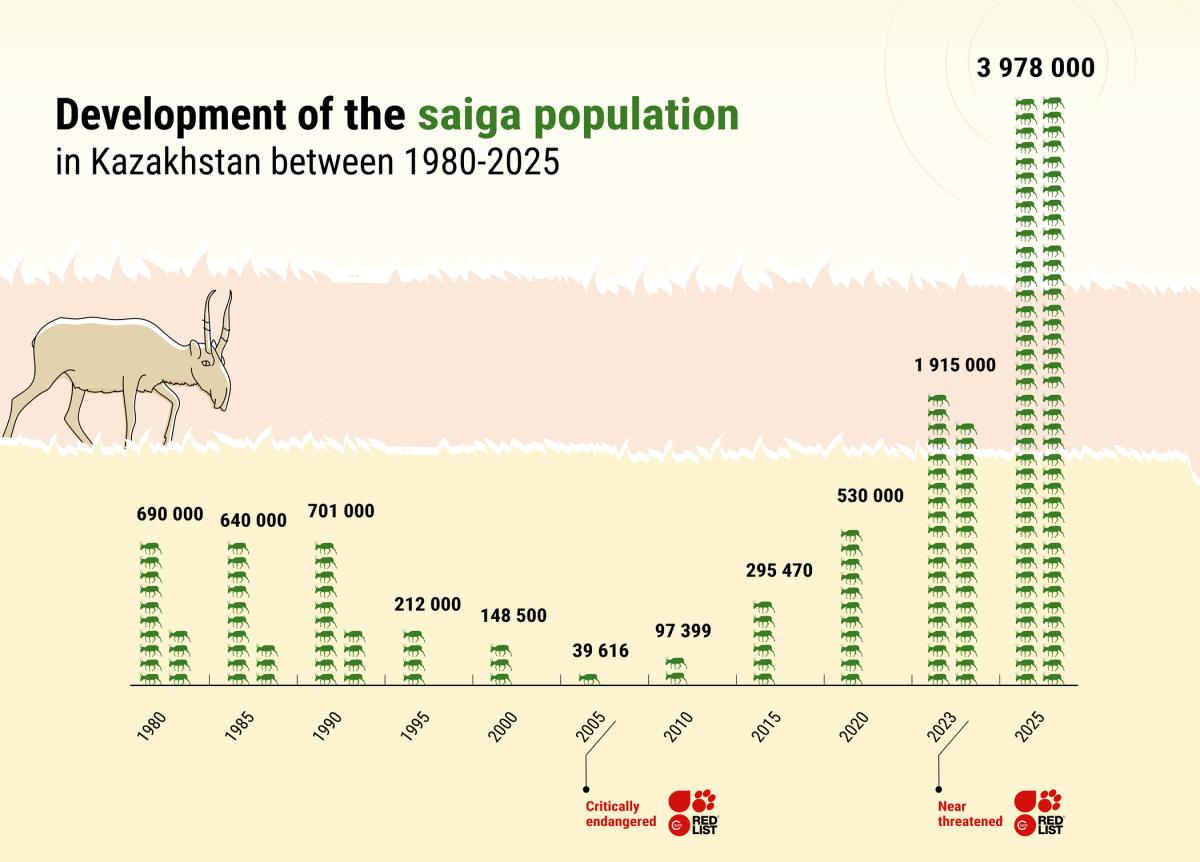

Saiga and humans have lived alongside each other for thousands of years. Historically, the antelopes have been an important source of food and skins for steppe communities, with no more animals being taken than the population could sustain. But after the breakdown of the Soviet Union in the 1990ies, poachers hunted male saiga for their horns to supply the Traditional Chinese Medicine market. The scale of the relentless hunting, alongside other pressures such as disease and habitat fragmentation from development, drove the saiga close to extinction. The threat of the saiga’s extinction was the reason for the FZS to support its conservation, finally integrated into the Altyn Dala Conservation Initiative with partners to aim for the conservation and restoration of Kazakhstan’s grasslands as a whole and thereby saving the species before it was too late.

Within only 10 years, saiga numbers plummeted by more than 95% to 21,000 in 2003; the fastest decline ever recorded for a large mammal species. Equally historic was their recovery when conservation stepped in – today, Kazakhstan is home to more than 3 million of the peculiar antelopes, and their conservation status was lifted from „critically endangered“ to „near threatened“.

Saiga horns, found only on males, are highly valued in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Organised gangs of commercial poachers can take thousands of male saiga every year, potentially resulting in a skewed ratio of remaining male and female saiga and a subsequent decreased reproduction.

Saiga are a holy animal and have traditionally been carefully used as a source of meat for nomadic herders and local communities. During Soviet time, industrial, strictly controlled use was in place. But illegal, uncontrolled hunting can lead to the species’ extinction as observed in the 1990ies.

New roads, railways, border fences and other artificial barriers cut through the migration routes in some parts of the saiga’s habitats, making it harder for them to find the food they need throughout the year.

In unusual climatic conditions of 2015, the outbreak of a bacterial disease caused a mass die-off in the saiga population. Over 200,000 saiga, 60% of the global population, died in one month, tragically illustrating their vulnerability to diseases.

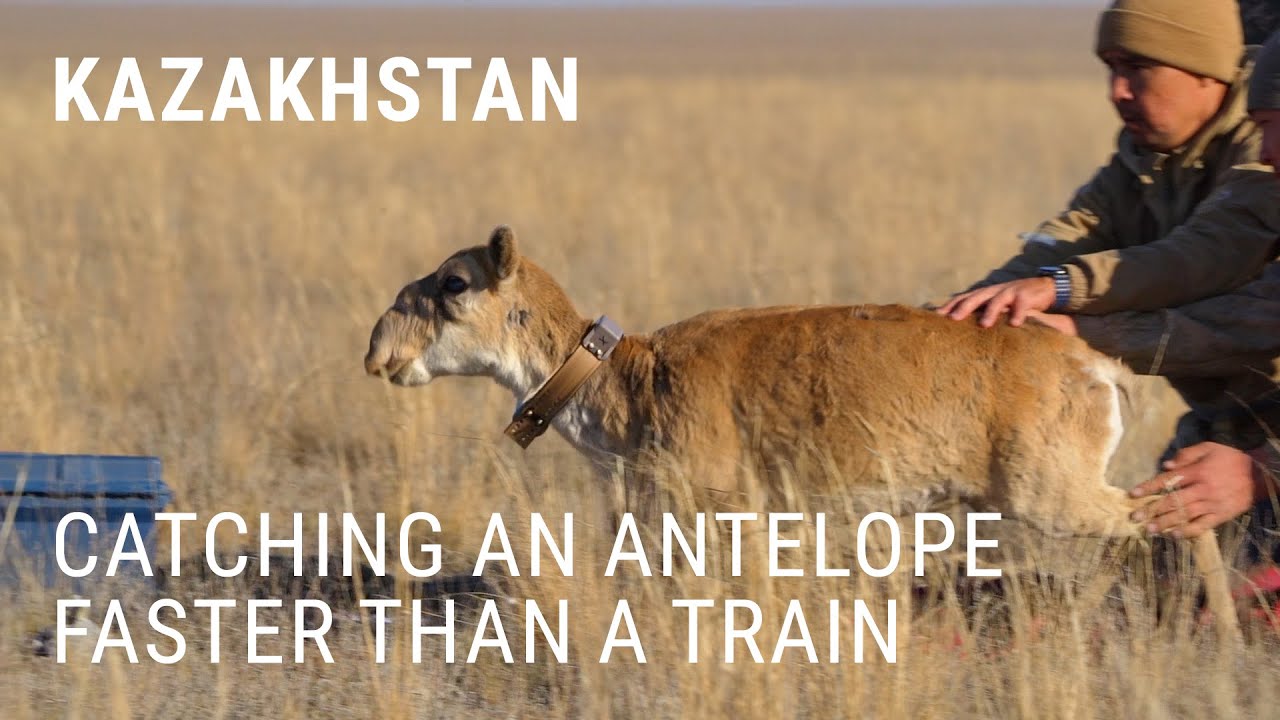

Saiga antelopes are a migratory species that easily moves up to 1.000 km annually. For this, they require connected landscapes to move safely between summering and wintering grounds. Understanding their spatial preferences in vast landscapes are is key to supporting saiga recovery effectively. Here is how we did it:

Safeguarding connected landscapes is especially crucial for the survival of migratory species, like the saiga. Based on extensive research on their movement, roughly 24,000 square kilometers of new protected areas and ecological corridors have already been created. Data from aerial surveys and GPS-tagged individuals feeds into the “Central Asian Mammal Migration and Infrastructure Atlas” and the atlas of the “Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration“. These are valuable open-access tools to support advocacy for migrating species across transboundary landscapes.