With a free online atlas created by over 80 scientists, you can track the routes of wildebeest, saiga antelopes, caribou, and other ungulates who make long migrations and see the man-made barriers affecting their journeys. The project is supported by FZS.

Altyn Dala Conservation Initiative contributes saiga data to global animal migration atlas

Small and shy by nature and with trunk-like noses, saiga antelope seem like unlikely survivors of the Pleistocene. Yet they’ve endured long after the mammoths and their other ancient megafaunal contemporaries went extinct. Today, the last stronghold for the species is the vast steppe ecosystem of Kazakhstan, which is home to about 98% of the global saiga population.

In the last few decades, saiga’s range has changed dramatically. After the Soviet Union collapsed, land use shifted and many people left remote rural areas that were no longer economically viable without Soviet agricultural subsidies. Weak wildlife protection and economic hardship for people in Kazakhstan led to an uptick in poaching, causing a 95% decline in saiga numbers in just 10 years. This brought the saiga to the brink of extinction.

But as people left, the grasslands had a chance to recover. In the early 2000s, Kazakh conservationists from the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK), the government of Kazakhstan and international NGOs formed the Altyn Dala Conservation Initiative to study and promote the recovery of the grasslands and its wildlife and to protect saiga from poaching.

“We didn’t know where [the saiga] were when we started,” says Steffen Zuther, biologist with the Altyn Dala Conservation Initiative. “Central Kazakhstan is the size of France… so we started this saiga tracking project to follow them on their migration and to understand which habitats we needed to protect and where are the places that saiga like to be and what needs our attention.”

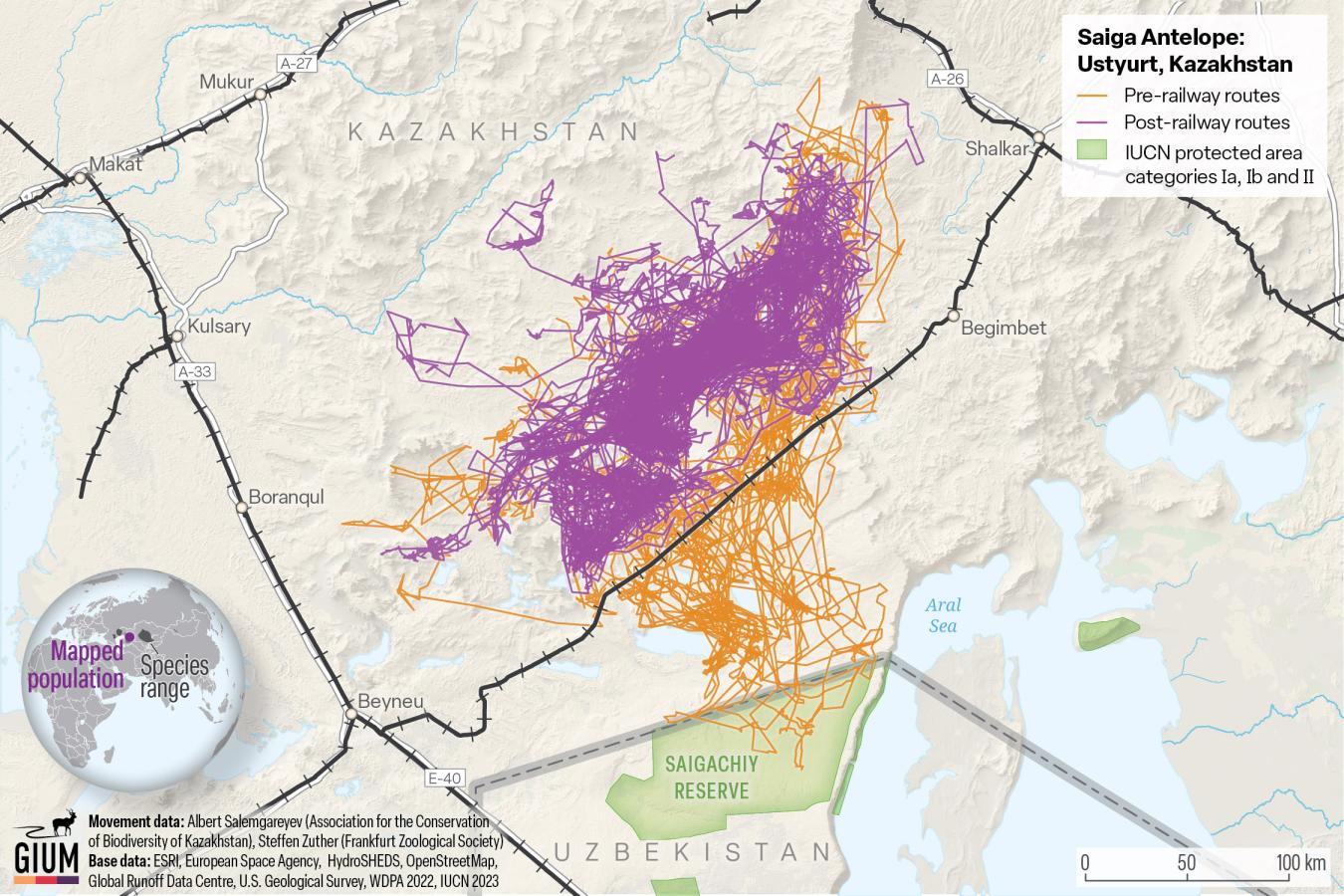

As the Altyn Dala field team and rangers started tracking saiga, they focused on the three populations in Kazakhstan: Ustyurt, Betpakdala, and Ural. Movement data revealed how hundreds of thousands of saiga make incredibly wide-ranging movements and long-distance migrations cross the steppe.

“As the population recovered, the movement also changed and they reoccupied areas they used to use before,” says Zuther. “Migrations were reestablished in this process.”

Saiga migrations can number in the hundreds of thousands. However, even as the saiga rebounded, they faced new challenges. In addition to illegal killing and disease outbreaks, landscape fragmentation and linear infrastructure pose the most serious threats to saiga migration.

We didn’t know where [the saiga] were when we started. Central Kazakhstan is the size of France…so we started this saiga tracking project to follow them on their migration and to understand which habitats we needed to protect and where are the places that saiga like to be and what needs our attention.

In 2015, the government constructed a major railway through central Kazakhstan, bisecting the Ustyurt population’s range. Tracking data from before and after construction illustrate how dramatically infrastructure can alter saiga movements, effectively cutting off 100 kilometers of their migratory range. The Ustyurt saiga stayed north of the railroad and no longer accessed land in the southern extent of their migratory range, which before 2015 served as critical winter range during harsh conditions.

One year later, conservationists with Altyn Dala learned of a new government proposal to fund a major highway cutting straight across central Kazakhstan. The trade route would connect China to the Caspian Sea, providing a faster way to transfer goods. Members of ACBK approached the government and presented tracking data they’d collected for years, showing how the migratory movements essential for saigas’ survival would be severed if the route was built as planned. Instead they argued to construct the route around the known saiga range.

Ultimately, the highway project was not approved, in part due to economic reasons. Planners determined the proposed route wasn’t financially feasible. However, this case illustrates the importance of animal tracking data, which offered empirical evidence of saiga movement and was an important tool in discussions with government planners. Tracking data allows animals to speak for themselves, showing people where they go and what habitats are necessary to critical parts of their lifecycle, such as giving birth and finding winter refuge.

Though this major highway through saiga range was ultimately canceled, new developments are expected to increase rapidly across the country and the region. Kazakhstan is projected to see significant development of roads and railways in the next decade, as multilateral businesses and governments aim to better connect trade routes between China and Europe through Central Asia. Much of this development is slated to impact saiga range.

When companies or agencies review development proposals in Kazakhstan, they typically request information on saiga and other wildlife impacts directly from ACBK, asking for the organization’s view on the project. However, Albert Salemgareyev, saiga expert from ACBK says there is no guarantee that projects will always be first referred to ACBK for environmental impact assessments, and Salemgareyev identifies a need to have tracking data readily available to development planners and government agencies.

“It’s better to make the information available to the public so planners and the government can use it right away without even needing to contact us… it will make life easier for us and for the planners.” That’s why the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration’s goal is to make tracking data and migration corridor maps not only public and accessible but integrated in environment agencies and development offices’ review processes. Thanks to conservationists and researchers with Altyn Dala, the migratory population of Ustyurt saiga is now one of 20 mapped populations available in the Ungulate Migration Atlas, a growing effort to document the world’s ungulate migrations and make corridor maps available to conservation planners.

“Planning processes are difficult to detect from the outside and to have this information communicated on the early side would be perfect and that is what we have hoped for,” agree Zuther and Salemgareyev.

Management is now focused on mitigating development and assessing if crossing structures will facilitate saiga movements safely across roads and railways, and whether truncated movements can be restored. GIUM aims to use the Atlas to stimulate research in effective mitigation measures to facilitate movement and to provide clearly delineate migration corridors for conservation.

Though development will continue as the human footprint expands, having reliable data on animal movement will help planners make decisions that meaningfully consider and accommodate migration, in Kazakhstan and around the world.

The atlas is now available at https://www.cms.int/en/gium/migration-atlas .