Our photographer Daniel Rosengren traveled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to take pictures of FZS work being conducted in Lomami National Park. An extraordinary journey to one of the most remote and difficult to access places on earth.

Finding wild bonobos

You can watch bonobos swing from tree to tree with their long arms quite comfortably at Frankfurt Zoo, a place easy to access from Frankfurt’s city center. But the real, wild habitat of these apes is anything but convenient to reach. The species live in rainforests, exclusively those found in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Preserving their habitat is an important aspect of the Lomami Conservation Project led by FZS since 2019.

Lomami is a landscape between Tshuapa, Lomami, and Lualaba rivers and is about the size of Switzerland. A quarter of this area is protected as Lomami National Park. The region is almost completely covered by dense tropical rainforests, which are home to bonobos, forest elephants, giant pangolins, and hippos. Numerous endemic or rare species have been scientifically recorded in Lomami, including Lesula monkeys, Dryas monkeys, Congo peacocks, and okapis.

FZS photographer Daniel Rosengren shares his journey into Lomami where he took photos that help protect the area.

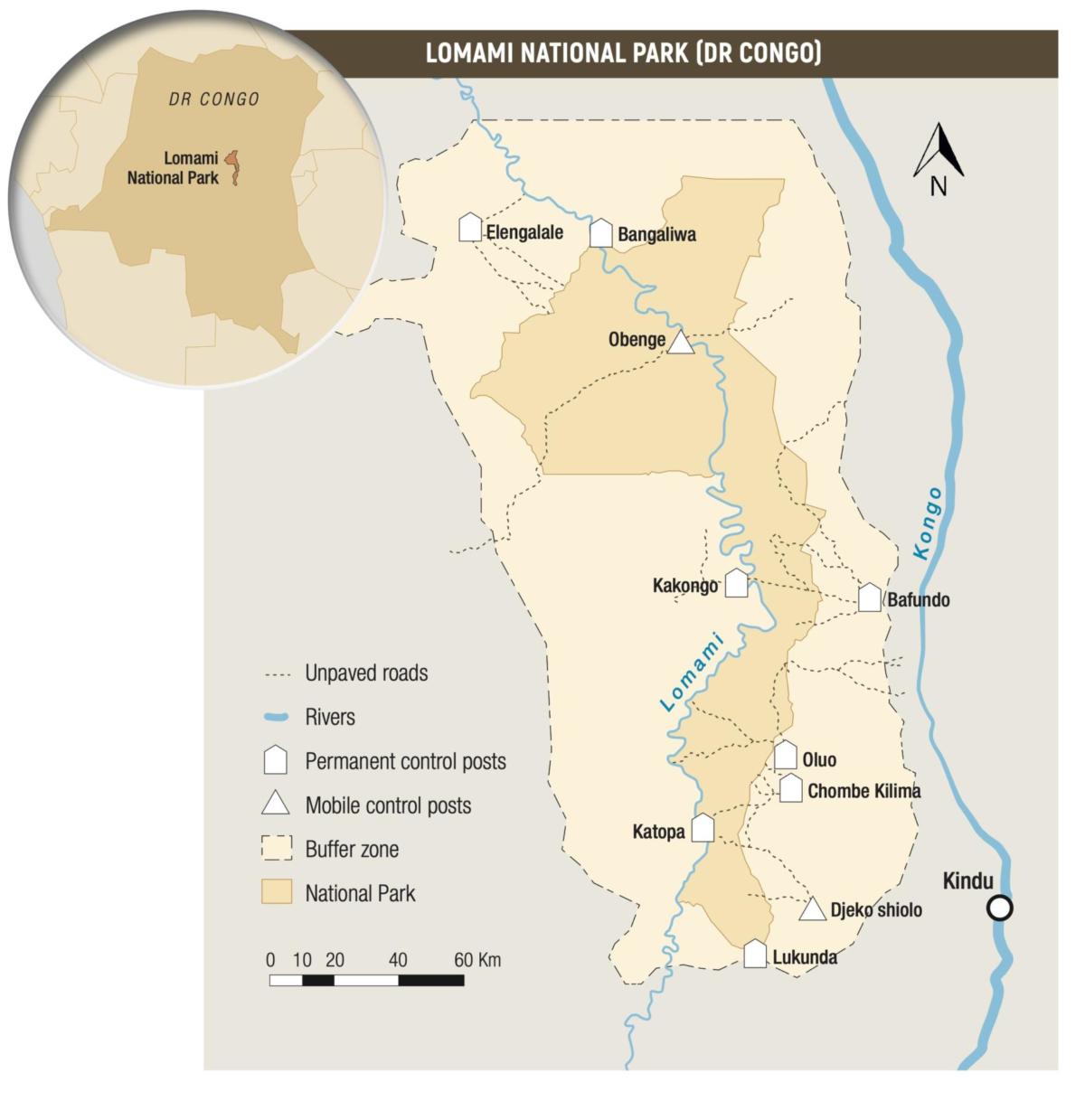

After arriving in the town of Kindu, the provincial capital in central DRC, I prepared for my trip to Lomami National Park with my Congolese colleagues. The FZS project operates from Kindu where the FZS office is located. On the map, I could see that the southernmost tip of Lomami National Park was around 70km away. How long it takess to cross that distance – this I would find out over the next few weeks.

Ephrem Mpaka (FZS team leader and my guide) bought the food and necessities we needed. We packed everything onto three motorbike taxis, basically filling up all the space in a big pile behind the driver. Ephrem and I had to squeeze in between the drivers and luggage on two of the bikes. For two days we traveled through villages, farmlands, and forests on narrow bumpy trails. Often the side vegetation whipped our arms and legs as we sped by. But the worst part was the butt aching and legs cramping from sitting in the same uncomfortable position for so long.

At one point we had to cross a river but there was no bridge. So, we packed ourselves and the bikes with the luggage in large dugouts that took us to the other side. At the end of the two days, we reached a tiny village: Chumbe Kilima. The last human outpost before reaching Lomami National Park.

The next day we had to start early as a long trek awaited, this time without motorcycles. Three porters were hired and when we left the village. Only wilderness remained. We followed a small trail led through the noisy rainforest where very loud cicadas and other insects made their presence known. Lots of birds were also singing but were very difficult to see in the dense vegetation. Whenever I stopped to look at something, my glasses instantly fogged up because of the high air humidity. I was constantly sweating. I tried to keep up with drinking water and adding extra salt to my food to make up for the salt lost through sweat.

We crossed a couple of rivers on simple, rickety bridges made from narrow logs with some added bamboo railings. We passed a few huge glades with tall grass; these were like different worlds compared to the dense dark rainforest. After nine hours we reached the Lomami River and crossed it with a dugout. On the other side was the small village; Katopa, where we set camp on the ranger station grounds. My GPS told me we had walked 37 kilometers that day, only five kilometers short of a marathon race. The wilderness of Lomami la before us.

One of the species I needed to photograph were bonobos. Together with the chimpanzees they are the closest relatives to us humans and can only be found in the DRC. But to find them was not an easy task and I wasn’t even sure I would encounter them at all. Finding anything in this forest was difficult. The vegetation was dense and blocked the view of most things beyond my immediate surroundings. On top of that, most animals are very shy and vigilant and move away before you even know they were there.

After about a week of exploring the area near Katopa, I started to lose hope. At one point, Ephrem said he heard the bonobos in a distance, but apart from that, we had no sign of them. So, we set out on a pure bonobo search. We deviated from the only trail in the area and started making our way through the dense vegetation. A man in front with a machete made it possible to move forward. Despite going at a pace of only around one kilometer per hour it was very tiresome. We constantly had to step over logs and twigs or dive under them and we often had to disentangle our feet when they got stuck in vines. The warmth and humidity kept us soaked in sweat. After a few hours without luck, we took a break and drank some coffee we brought in a thermos. As we sat there in a small clearing created by a forest stream there was a general feeling of yet another failure and the mood was down.

Just when we were about to leave, we heard some screams and calls that were undoubtedly bonobos. They were near. We tried to get closer without making much noise. This meant not using the machete much and trying to avoid touching any branch or vine. This was an impossible task, but apparently, we were quiet enough, because suddenly, there they were, high up in the trees, feeding.

It was a small group and they were difficult to spot through the vegetation. I found an opening where I could see and photograph a male. But they were aware of our presence and soon moved away, with ease. I followed alone to make as little noise as possible. They hadn’t moved far and when I found them, I got a few more minutes with them before they moved away and disappeared where I couldn’t follow anymore without a machete. I felt relief and great joy. Relief because these were of course important photos to get for the project and joy because of having seen these amazing animals in their own environment. A moment of pure luck!

Towards the end of my 5.5-week stay in the country, I started feeling sick. I had a fever, some joint pain, and a bad stomach. It was most likely malaria. The previous two days we had walked straight out in the forest from the main river. I was very weak, but now we had to start my journey home. We would try to walk back to the river, but I really wasn’t sure I would be able to. I had no appetite at all, just the thought of rice and beans made me feel queasy. Suddenly, we found bonobos but I didn’t have the energy to even hold up the camera long enough to take photos of them. I had to sit down and rest after trying.

These bonobos belong to a different population than the ones I had seen a couple of weeks before and they are separated by the river Lomami. An interesting fact is that the bonobos east of the river never get malaria while the ones on the west side do. I didn’t reflect on it at the time, but there I sat, with malaria, watching my evolutionary cousins that are also susceptible to malaria.

When we moved on, I moved very slowly and slowed down the group. After a while, I said I needed to rest and sat down by a tree. But even sitting felt too exhausting and I lay down on the forest floor. The others patiently waited. I tried to eat a power bar but only managed half. FZS Project Assistant Koko Bisimwa offered a cup of tea with a lot of sugar in it and I slowly drank it all. It would be safe to say that the sugar in that cup saved me. It gave me enough energy to continue and make it all the way back to the river where a dugout waited. It was a great relief to sit down in it. I really wasn’t sure I would make it until I got there. We had walked exactly 16 kilometers in just under 7 hours. The rest of the day we spent traveling down the river Lomami.

This was the first day in my 10-day exit plan to leave the Park and get home. The next morning, I felt better, the malaria medication I was taking seemed to work.

After another day on the river, we reached a village and I got to sleep in a bed for the first time in a month. Then two days on a motorbike followed. After a negative corona test in Kinshasa, I got on the plane and flew home.

This trip to DRC was unique and my most exhausting trip as the FZS photographer to date. Once home I slept a whole day and night straight. I then weighed myself because I noticed that my trousers had become loose. Sure enough, it turns out that I had left behind 10% of my body weight in DRC. But it was worth it.