The most extensive forest area in Vietnam is found in the central part of the country. It is half the size of Luxembourg spanning about 1,200 square kilometers and encompasses two FZS supported projects, Kon Ka Kinh National Park, and Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve. This is a biodiverse and culturally rich place that is home to rare primate species.

Where the rare apes are

Marco, our podcast host, recently spoke with Dr. Long Thang Ha, FZS project leader in Vietnam, about Kon Ka Kinh National Park and Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve. He wanted to learn more about the rare primate species living in those areas and the community work that takes place there.

Dr. Hà Thăng Long is FZS’s project leader in Vietnam. For the past eleven years, Dr.Long has helped prepare the establishment of a biosphere reserve – a milestone in nature conservation for the country that was implemented in 2021.

Hello, Dr. Long. Can you tell me which primates live in the FZS supported protected areas in Vietnam?

Sure. The area is quite diverse. In Vietnam, we have 25 primate taxa which can be divided into four groups. A small ape called gibbon, the Macaque, the leaf monkey Colobinae, and the nocturnal primate lorises.

For me, the grey-shanked douc langur. This is mainly because I have spent almost 20 years studying them, focusing on their behavior and the population, so I know a lot about them. Now I am pleased to say that we have a long-term project to safeguard them in Kon Ka Kinh National Park.

Actually, the grey-shanked douc lives in a larger landscape. They live in all six provinces in Vietnam. Kon Ka Kinh is just one part of the six provinces. But the species is endemic to only that region in Vietnam. So, the douc lives also in the other regions, but the thing is this population is disconnected by agricultural fields and hydropower station dams. Also, the development of infrastructure has created two separate populations, where Kon Ka Kinh has one population that is valuable, and it can be a stronghold for the population in the future because the number of individuals is quite large. Also, we support the park, and the community is focused on protecting this species.

At Frankfurt Zoo, we also have the gibbon, a closely related species to the one you have at Kon Ka Kinh. Do you know how many gibbons and douc langurs live in those areas?

Yes. I will talk about gibbons first because I have also seen this species at Frankfurt Zoo just yesterday. In Kon Ka Kinh National Park, we have a sister species, the yellow cheeked gibbon with the scientific name Nomascus annamensis. It is specific to the region, to central Indochina. There is a large number of these gibbons in my area. In the last survey, we counted around 40 groups and about 120 to 140 individuals.

While for douc langurs, the last survey conducted for this species was in 2020. At that time, the population was estimated to be between 1,200 to 2,000 individuals.

Yes, the douc lives in big groups, which sometimes can be hundreds of individuals, especially when they gather in places with a lot of food or to mate.

Gibbons however live in quite small groups, between three and five individuals, and they live in a family structure like us. When young gibbons are about three years old, they leave the group. Especially male gibbons will do this because they are also very territorial animals. Using their voices, they sing every morning and essentially communicate “I am here, and don’t come to my territory if you are not a friend”.

You can also hear the singing in the zoo in the mornings. It's beautiful. And I assume you can also hear them in Kon Ka Kinh?

We have a specific surveying technique. We go into the forest and try to find a high mountain where we can clearly hear the vocalizations of the gibbons in the early morning. Then, when we pinpoint where they are in the forest, we go there and use the voice recorder to record their songs. This way we can distinguish distinct groups because each individual group has different structures and frequencies in its songs. By doing this we can distinguish the group and individuals. We then survey the whole park, and we can calculate how many of them are in the forest.

Using camera traps is impossible with gibbons because the animals move in the upper forest canopy. Camera traps capture images using movement, and since branches move a lot at that height, it is difficult for the camera trap to capture the animals. Instead, most of the pictures will just be tree branches. A better way to locate the gibbons is by listening and using a sound recorder so that we can analyze individuals and groups.

Like in any developing country the living conditions of people living in rural areas, especially in mountainous areas, is still poor. Hunting is one way the local people can get food and then sometimes they can sell it to earn money. Hunting is the biggest threat to the primates, both to the gibbons and the douc because otherwise there is no way to catch them. Using a gun is the only way you can hunt a primate.

We have a couple of different approaches. First, we try to prevent hunting in protected areas. This means we work closely with park rangers supporting them to do more frequent patrols, collect more information on the gibbon, the douc, and other primates and work with local communities, helping them understand that this species is becoming exceedingly rare.

We also offer workshops and courses to children in the communities. There, they learn about the importance of these rare species and that they should not be hunted or eaten.

We also try to help local people find alternative sources of income. For example, helping them find work as tourist guides. This way they do not need to rely on getting their income from hunting

Fortunately, the situation is slowly changing. People are realizing that they can earn money without having to kill and sell animals.

By working so closely with the local communities, you also go into the village and talk to the people, right? Could you keep up your work during COVID?

Fortunately, during COVID the project activity was still running. Of course, we had travel restrictions which meant that our team from the Danang FZS office could not travel to Kon Ka Kinh National Park very often. Fortunately, in the past five years, we have built good relationships with the Bahnar people, a local indigenous group. We have been sharing educational material with them about wildlife protection and information about alternative methods of earning money. We were able to build a playground for the children and create a library for them before the pandemic. During the pandemic, we spoke with them by phone, and they organized conservation work themselves.

Is it also easier to get your message across when the Bahnar people leaders are included in your work?

Yes, but like anywhere else, it takes time to really build trust between the project members and the local community. In the past five years, we have been traveling with Bahnar representatives, going to different villages, and speaking to many people. We also play soccer and volleyball with them, choosing team names that represent local wildlife. This is both fun and gives us a good chance to talk to each other about those animals.

This is a creative and inclusive way to get people involved. You cannot just go somewhere and tell people what to do. The Bahnar have a valuable culture that is unique to the rest of Vietnamese society. We are also allowed to participate in their cultural festivals where they perform their traditional dance. At such events, it is much easier to talk with one another in a more relaxed environment about sustainability and conservation.

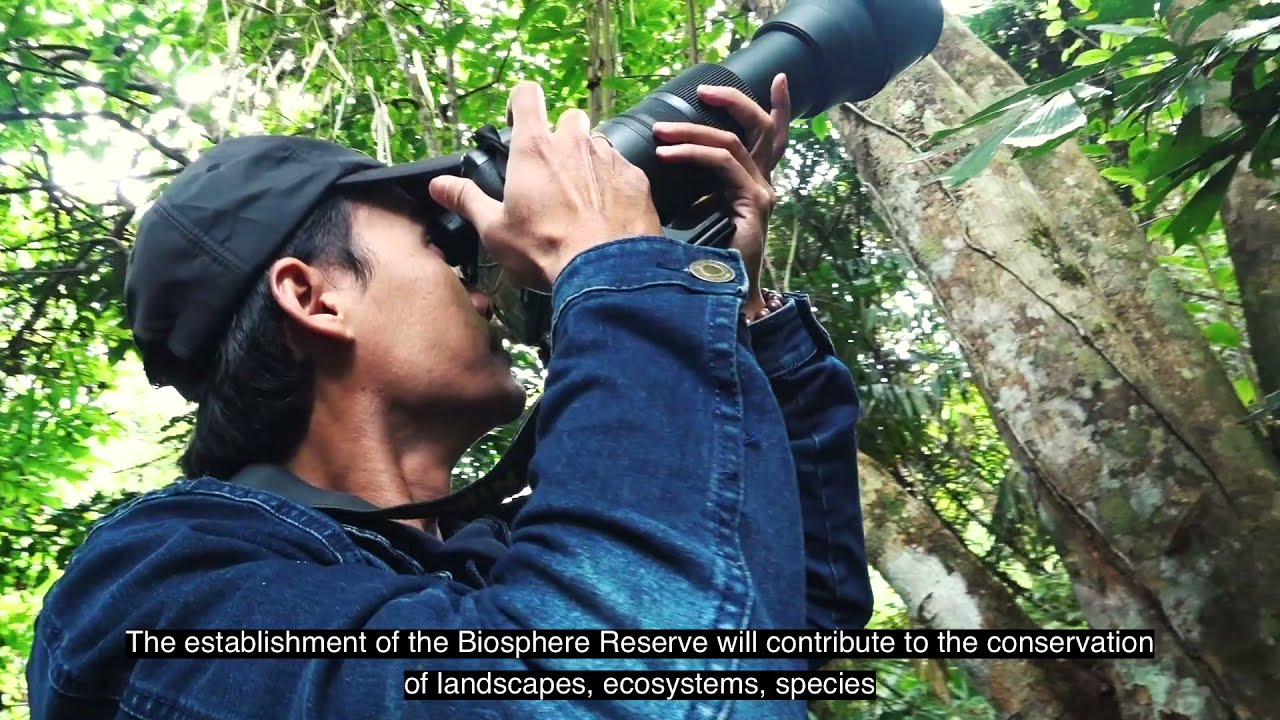

That brings me to one of the most important achievements that took place for this area in the past few years. On September 15, 2021, UNESCO established a new Biosphere Reserve in Vietnam which includes Kon Ka Kinh and Kon Chu Rang. But what exactly is a biosphere reserve?

A biosphere reserve is an area that is much bigger than a national park and nature reserve which contains natural habitat for species, wildlife, and for humans. The national park is more about wildlife, but the biosphere reserve includes humans. The biosphere covering Kon Ka Kinh and Kon Chu Rang is now 4,000 square meters in size, which is 10 times bigger than Kon Ka Kinh and is a huge landscape for wildlife that is under the management of the biosphere reserve.

Also, the biosphere supports people who live in the area to develop in a sustainable way. So that humans are included in the management process of the biosphere.

Video of the Kon Ha Nung UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, created by VTV8, a Vietnamese TV channel.

Copyright: Mr. Nguyen Hai Thuy, VTV8 filmmaker.

As of 2021, there are 727 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves located in 131 countries around the globe. These Reserves cover about 5% of the planet’s landmass, which is almost equivalent to the size of Australia. About 257 million people live in Biosphere Reserves worldwide.

Biosphere Reserves unite people’s needs and nature protection. They are places where scientific and local knowledge are combined with citizen participation in management and planning. The ultimate goals are to: reduce the loss of biodiversity, improve local livelihoods, and enhance social, economic, and cultural conditions in an environmentally sustainable way.

This uniting of needs makes UNESCO Biosphere Reserves different from the commonly known UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites which are specific exceptional places that are often physical or biological formations or areas that contain habitats for threatened species of animals and plants.

You said that Kon Ka Kinh National Park and Kon Chu Rang Nature Reserve are both part of it and in both protected areas there are gibbons, so does the biosphere reserve also build like a corridor between the two areas?

Yes, exactly. The National Park and Nature Reserve became the two core zones in the biosphere. A core zone means that this is the part of the biosphere where there is high biodiversity value.

The corridor between the two core zones is an area where we also see gibbons. Gibbons and other wildlife could freely move with certain protection between the two areas in the past but now as a biosphere reserve, the area has higher protection that is enforced by both local communities and at provincial level. That is a good thing for the region because it is not only the core zone but also the connected area that is also being protected.

It took us 11 years to achieve this goal. In the beginning, when we started to work in Kon Ka Kinh National Park we already knew that the Park was only one part of a larger landscape of tropical forests that is home to about 1,400 species of plants and 300 species of mammals. So around 2,000 species live in that landscape, with some species found nowhere else in the world.

For example, the nocturnal pygmy Loris has become rarer now because people hunt it heavily. But in Kon Ka Kinh National Park and Kon Chu Rang you can see them very easily in the evening.

Thank you very much for this interview, Long.

-

Vietnam

Vietnam

Kon Ka Kinh and Kon Chu Rang