Last November, FZS supported a transport of kulans to the Torgai steppe in central Kazakhstan for the third time. Veterinary student Anne Dohrmann took part in this translocation. In freezing temperatures, she spent many weeks at the remote reintroduction site and ranger station “Alibi” to observe the new arrivals

Four kulans for Alibi

„There! They’re coming! They’re here!”

A tiny speck of pulsing red light has appeared just above the horizon of the southern sky, contrasting to the dark grey afternoon haze.

A jolt of excitement surges through me. Along with me, some 25 rangers who have been eagerly awaiting this moment all day, spring to life. Fingers are being pointed towards the light, growing stronger now, vehicle engines started and shouts for astray colleagues bellowed across the steppe.

Already we can hear the dull thrum of the helicopter, faint at first, but growing louder with every passing moment. Only few minutes lay between its first appearance as red dot in the distance to the large Mi-171 helicopter hovering just above our heads. Carefully it starts lowering itself carefully onto the shaking grass, the sound of its powerful engine reverberating through the air.

As soon as it is squatting safely on the ground, a small door pops open, and out jumps Albert Salemgareyev, the kulan translocation project coordinator of our Kazakh Partner ACBK (Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan). Emerging from the impressive machine, he appears tiny, and is soon joined by more tiny, bustling figures. While the noise of the helicopter slowly dies, other sounds arise: the metallic clanging of heavy cargo doors being opened, the rustic stuttering of an elderly tractor approaching from afar and above all the mingling of many excited voices shouting instructions in Kazakh and Russian.

Four young kulan, or Asiatic wild ass, have just arrived to “Alibi”, a field station and reintroduction center in central Kazakhstan. Alibi lies embedded in the vast steppe area that FZS works to protect with national and international partners. In 1930, its last native kulan was shot. Now the endangered species is experiencing a comeback. As FZS’s delegate on site, I am here for the third kulan transport conducted by us and our partners.

The road to a self-sustaining kulan population in central Kazakh grasslands is still long. This year, we have edged a little closer to this goal.

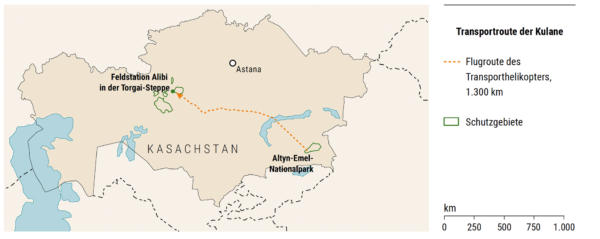

Just like me, the translocated kulans are experiencing real steppe environment for the first time. The wild ass come from the rocky National Park “Altyn Emel”, which holds the largest kulan population globally and is located in the far south-east of Kazakhstan. So far, poor road connection have made a helicopter lift the only feasible option to transport these big animals 1,400km across the country.

Peeking through a narrow slit at the top of one of the boxes I glimpse the attentive play of long, slender ears, back and forth, trying to make sense of the busy sounds around them. One might not guess that these animals have just completed an exhausting journey of almost ten hours. Some uncertainties accompanied their trip and we are glad to have them here on safe, central Kazakh grounds now.

As opposed to the previous transports there was no possibility to individually handle the kulans pre-boxing. The veterinary supplies commonly used for immobilizing large wildlife are currently not permitted in Kazakhstan, giving us quite a headache how to steer around this obstacle. A vet from Kazakhstan, experienced in the national legislation and practicalities for moving kulans, assisted us on site and provided our chosen animals with a mild sedation to ease their transportation stress. The procedure went well and showed us it is possible to transport the kulans with less potent medical drugs, although a direct handling stayed impossible.

The night following the helicopter’s arrival to Alibi, a persistent snow front settles onto the steppe, locking the aircraft and crew to the ground for over a week. While glad to have gotten in four kulans just in time, we have to cancel the planned second transportation as no reliable improvement of the situation is to be expected.

We were aware of this risk. Earlier in October, Albert Salemgareyev and Alexander Putilin, two members of ACBK, joined a Government-led transport of kulans over land in order to explore the feasibility of this method. This crucial missing link in the road network is to be completed early 2023 and will end our dependency on weather conditions.

Building a coherent group of wild asses is inherently complicated. Individual interactions and sympathies are hard to predict. In order to learn more about this and document any developments, I stay at the remote ranger station. While being awed by the steppe’s everyday beauty, the kulan situation takes a shocking turn: after few days, the stallion suddenly attacks two of the new kulans fiercely and relentlessly. Aggressive behaviour of this intensity was not known from wild kulans before, and even less anticipated in this particular stallion, as it had been very peaceful with other kulans so far. Both animals die subsequently from their injuries.

Wildlife reintroductions, especially of large species with complex, highly developed social structures like kulan stay unpredictable to a certain degree, despite meticulous and careful planning. Not even a skilled and well experienced team such as ours, with national and international experts, is immune to the risks such a venture holds. Once more we are reminded of the big struggle that comes with mending and recovering what has once been lost.

Bringing in more kulans remains our main goal for 2023. This time on land. Aviation for kulans is not completely off the table though: animals from European zoos shall be brought to Kazakhstan in the next years as well, to mitigate in-breeding.

Leaving the six kulans in the enclosure to the caretakers’ keen eyes, we bump along the frozen steppe tracks back to Astana. I gaze out the window onto the endless plains, now still and sparkling with frost. “One day, there will be kulans here again,” I think to myself and smile. The road to a self-sustaining kulan population in central Kazakh grasslands is still long. This year, thanks to the commitment of our team, Kazakh partners and our supporters in Germany and beyond, we have edged a little closer towards this goal.

Anne Dohrmann studies veterinary medicine in Leipzig, Germany, and works as an assistant in the reintroduction project for the kulan. All watercolors in this article were painted by Anne during her time at the field station.